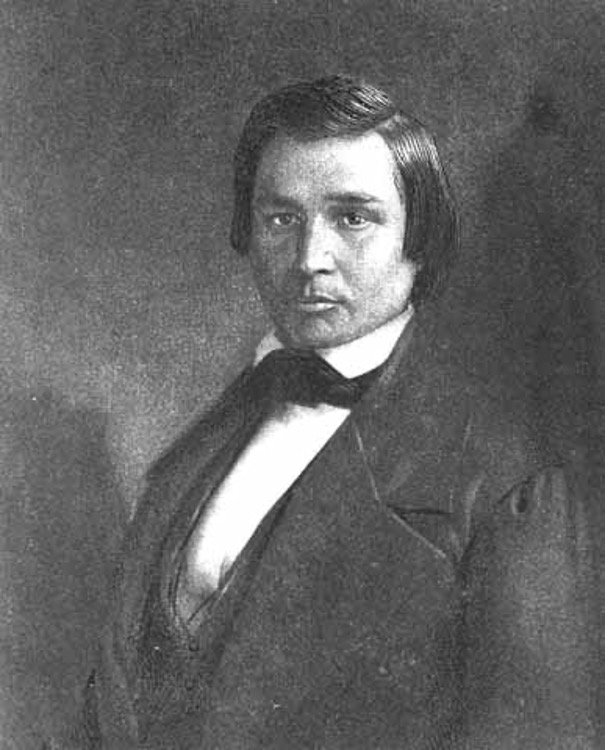

George Copway (Kahgegagahbowh), 1850. Canadian Encyclopedia, courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

The Anishinaabeg and the Three Fires Confederacy

It is my view that Anishinaabeg Nations had practised and knew of a form of democracy that resembles “direct democracy” even in times of old (pre-contact). The primary unit was the Band, comprised of a number of different Dodems (Clans) and often two or three of the “fires” of the Nation—Bodewaadmig (Potawatomi), Odawag (Ottawa), and Ojibweg (Chippewa)—within a single community.

These Bands claimed and “ruled” (or cared for) large tracts of land, often equalling millions of acres. In the Huron County region and the Huron Tract as a whole, the Huron Tract Treaty Nations include Kettle & Stony Point, Aamjiwnaang (Sarnia) and Walpole Island (Bkejwanong). Other Anishinaabeg Nation Treaty partnerships who signed treaties with the British exist all around the treaty territory (e.g., Longwoods and the Saugeen surrenders).

Perhaps the most important aspect of this form of democracy is the direct and lasting relationships among individuals and representatives of Bands as they interact through ceremony, both political and personal. Respect (Minaadendamowin) and Humility (Dibaadendziwin) permeate every interaction. From the sweat lodge to funerary rites and everything in between, the ceremony of Council and decision making were to occur with the good of each individual in mind, and with foresight about the interests of future generations.

Today, First Nations enjoy direct and immediate representation in the form of their First Nation Councils, including Anishinaabeg governments at Saugeen and at Kettle & Stony Point.

Historically, according to George Copway, Anishinaabeg peoples, like all peoples and nations in this world, had “rulers” and they were “inheritors of the power they held. However, when a new country was conquered, or new dominions annexed, the first rulers were elected to their offices. Afterwards, the descendants of these elected chiefs ruled the nation, or tribe, and thus the power became hereditary. On the death of the chief ruler, should the son be under age, the brother of the deceased rules in his stead, until the youth became a man, when after the display of much ceremony, he takes his seat at the head of the council of the nation. These young rulers are apt to be more cautious in the exercise of their governing power than those who possess more mature age with its more mature vanities” (Copway 140–41).

Map 6. Source: Union of Ontario Indians, https://www.anishinabek.ca/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/.

“Full-blooded Chippewa Man,” 1918. National Endowment for the Humanities

The Anishinaabeg peoples are a loosely confederated national association of self-determining peoples who live within the national and state bounds of both Canada and the United States of America today. They comprise the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa. Other names used in treaties with Britain, Canada, and the United States include the Ojibwe, Chippewa, Mississauga (various spellings), and Saulteaux.

The Three Fires Confederacy is named as well in the treaties. Also called the Council of the Three Fires, it was an alliance of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations who comprised the essential component parts of the Anishinaabeg Nation. Although Anishinaabe peoples and Bands formed Clans and Nations prior to contact, it is likely that the modern form of Anishinaabeg confederate unity formed some 500 years ago as a defence against the growing expansionism of the Five Nations Iroquois Confederacy based in New York State. Colloquially, the Ojibwe are Keepers of the Medicine and Faith, the Odawa are Keepers of the Trade, and the Potawatomi are Keepers of the Fire, although all Anishinaabeg Bands share in these “gifts” and possess characteristics of all three “Fires,” which denote a kind of constituent nationhood, similar to the “states” in the United States of America. It is important to note that Indigenous peoples formed alliances such as these well before contact with Europeans, but colonial influence magnified and often expanded urgency for “inter-tribal” unity or in some cases disunity.

Looking at Anishinaabeg Nation history is a powerful exercise of seeking understanding of historical connections to present. According to the Anishinabek Nation political organization, the history of the First Nations and peoples in southern Ontario can be described like this:

By the mid 1700s, the Council of Three Fires became the core of the Great Lakes Confederacy. The Hurons, Algonquins, Nipissing, Sauks, Foxes, and others joined the Great Lakes Confederacy, and after the Treaty of Niagara of 1764, which marked the formal beginning of the peaceful relations with Great Britain, this powerful body provided the British with important allies in times of war and a balance to the Iroquois Confederacy to the south and east” (Anishinabek Nation).

The Confederacy had a number of meeting places but “one of the most used and the most central was Michilimackinac” (UOI-Anishinabek Nation). The Anishinaabeg moved southward and identified the land around the southern end of Lake Huron as Aamjiwnaang, which extended from the Maitland River (Goderich) around the lake to the Flint River in Michigan (see https://www.aamjiwnaang.ca/history).

Eventually other nations joined the Confederacy, which today is known as the Anishinabek Nation, extending from the north shore of Lake Superior to the St. Lawrence River. Map 6 is from the Union of Ontario Indians website (“Anishinabek nation”).

The Anishinaabeg people were the only ones who signed the Huron Tract Treaty #29 (as “Part of the Chippewa” or Ojibwe Nation), which laid the groundwork for European settlement of today’s Huron, Perth, Middlesex, and Lambton counties. The idea that all of southwest Ontario was entirely “Neutral Iroquois” territory is highly unlikely even into the immediate era prior to the Beaver or Iroquois wars. It is my belief that Huron County truly was a “Land Between” (Sherratt), in that “non-Six Nations” (Hurons and Neutrals), Iroquois-speaking peoples, and the Anishinaabeg often lived in peace and were at times at war, but at all times in close proximity, making the Dish with One Spoon concept necessary for harmony. Indigenous history is complex and much is hidden from simple and quick understanding. Sometimes, concepts have to be understood through a slow progression of knowledge acquisition. The Huron peoples whom Champlain encountered were likely not the Neutral or Attawandaron peoples we recognize as having lived in ancient Late Woodland Huron County, but they were related and connected through trade, marriage, and political engagement. The same can also be said of the Hurons and Anishinaabeg. The shores of southeastern Lake Huron were and still are home to elements of Anishinaabeg, Neutral, Huron, and Six Nation Iroquois, and even many generations of Métis.

Sources

Belshaw, John Douglas. Canadian History: Pre-Confederation. 2nd Ed. BCCampus. Victoria, BC. https://collection.bccampus.ca/textbooks/canadian-history-pre-confederation-2nd-edition-bccampus-68/

“First Nations of Simcoe County: A History.” Innisfill Historical Society. https://firstnations.innisfillibrary.ca/

“Huron-Wendat”. Canadian Encylopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/huron

“Wyandot Warriors.” https://www.legendsofamerica.com/wyandot-huron-tribe/