Map showing treaties in southwestern Ontario. Source: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/treaties-huron-county/

European Contact, Treaties and Agreements

The history of treaties among Indigenous peoples and European nations is fraught with controversies that are still felt deeply today. Contemporary relationships between native and non-native governments in North America are defined, to a large extent, by disagreements over documents that are between 100 and 300 years old.

These documents are still sacred and lasting though. We will not attempt to address them on this website and couldn’t within this limited space even if we wanted to, but a picture of clarity with respect to this region’s history, and its relationship to higher principles of First Nation–European agreement making is hoped for. As a treaty researcher, I am constantly fascinated by the legal “black hole” that seems to exist as a result of the treaties as a whole, even looking at one treaty at a time, such as our treaty for this area of southwestern Ontario. Not only do original treaties exists but “sub surrenders” or sub-treaties exist that chip away at First Nation sovereignty (e.g., Treaty #69 and #71½). I am grateful that my ancestors entered into respectful relationships based on a desire for truth and collaborative living, learning, and sharing with colonial settlers and their descendants.

Sam George with the Huron Tract Treaty (Rough Cut)

The concept of agreements, alliances, and cooperation was not new to First Nations when the Europeans arrived, as we have seen in previous sections on the Three Fires Confederacy, the Huron/Wendat Confederacy, and the One Dish One Spoon agreement. The treaties are also important historical documents because their signatures shed light on which Indigenous leaders were speaking for which people regarding which territories at a particular time in history.

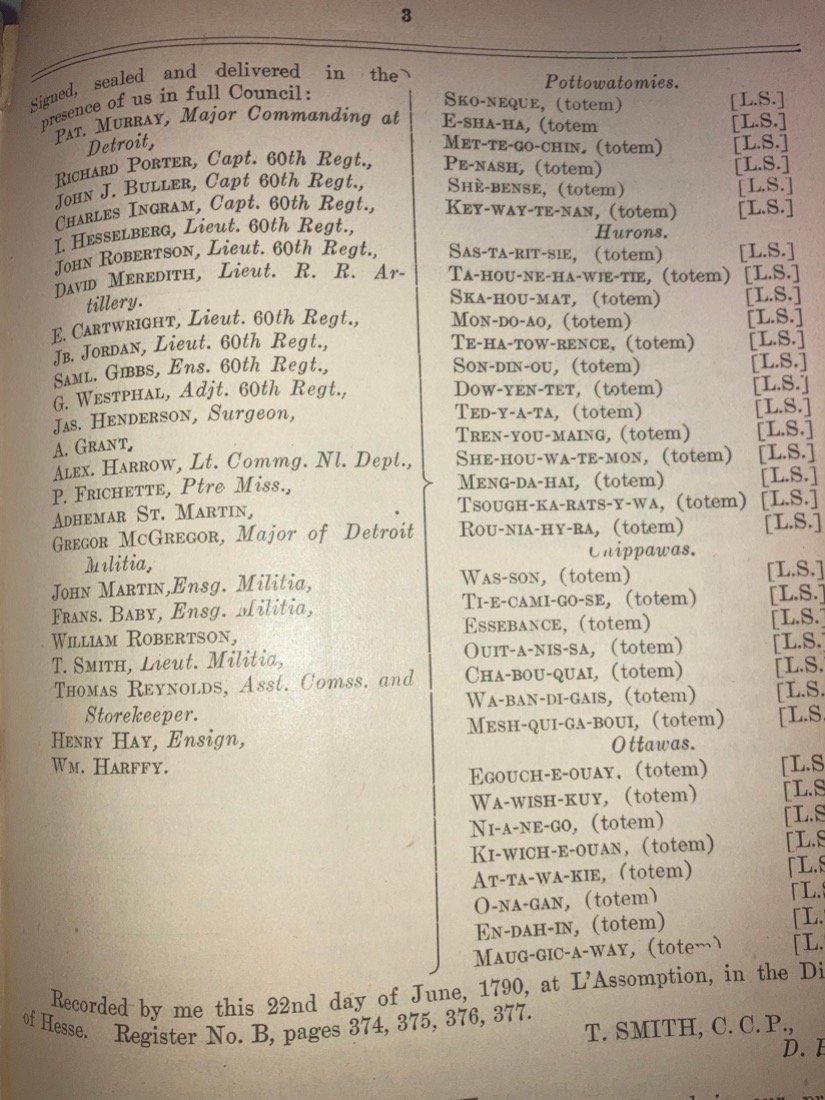

Name register of signatories to pre-Confederation Treaty #2, just below modern-day Huron County, where Anishinaabeg and Iroquois signed the same treaty. Thirty-seven years later, the land upon which Huron County would be built was ceded/surrendered by only Anishinaabeg Bands.

The first Europeans to meet Indigenous people on the eastern shore of Lake Huron were likely Étienne Brûlé and his companions in 1610. These early explorers kept records of their journeys, but it is also possible that coureurs des bois from New France (Quebec) had come in contact as they sought trade in beaver pelts with Indigenous groups.

Historic plaque commemorating the early exploration of Huron County, Huron Tract, Treaty #29 signatories.

Explorers were quickly followed by Catholic missionaries, who were also adept at recording their observations. These have left us valuable early descriptions of Indigenous cultures. For example, Father d’Aillan, a Recollet priest who lived among the Attawandaron, or Neutrals, in 1626, described them as “physically the finest body of men I have seen anywhere” (Yates, “County History”). Father d’Aillan was also impressed by their methods of government and social organization. Even with the best of intentions, objective observation is impossible and cultural understanding is always influenced by our own perspectives. This is equally true of Indigenous descriptions of Europeans. Mutual understanding is always an ongoing and incomplete process. It takes effort and patience, but it is our only alternative to fear, suspicion, and animosity. It is clear, however, that the Anishinaabeg people in this region have had social and political intercourse.

In broad terms, the early years of European contact in Upper Canada (about 1600 to 1800) were focused on controlling trade routes and goods, while efforts at “permanent settlement” began many decades after the British Royal Proclamation of 1763, into the 19th century. The Royal Proclamation is significant because it explicitly states that Aboriginal title has existed and continues to exist, and that all land would be considered Aboriginal land until ceded by treaty. The Proclamation forbade settlers from claiming land from the Aboriginal occupants unless it had been first bought by the Crown and then sold to the settlers. The Royal Proclamation further sets out that only the Crown can buy land from First Nations. Anyone wishing to establish permanent settlements had to receive or purchase land from the Crown, and all treaties with First Nations were with the Crown. In the case of the Huron Tract, then, the land was purchased from the Crown by the Canada Company. Treaties #29 and #45a with the Crown covered the agreement with the Indigenous people, in this case the Anishinaabeg. With these two legal requirements in place, the Canada Company could then sell land to the Dutch Baron van Tuyll (Carel Lodewijk, Baron van Tuyll van Serooskerken), who proceeded to establish the settlements of Goderich and Bayfield by selling parcels to new immigrants, largely from the Netherlands, Scotland, Ireland, England, and Germany.

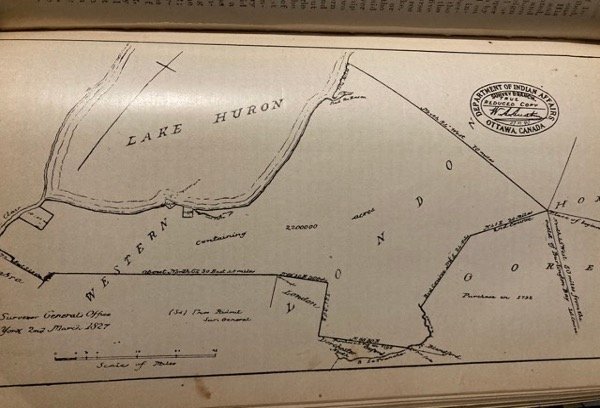

True reduced copy of map of Treaty #29 with “a part of Chippewa Nation” and British Crown representatives. Modern Huron County is situated near the top of treaty area (large portion of land connected to the southeast shore of Lake Huron, top left portion of outlined treaty area).

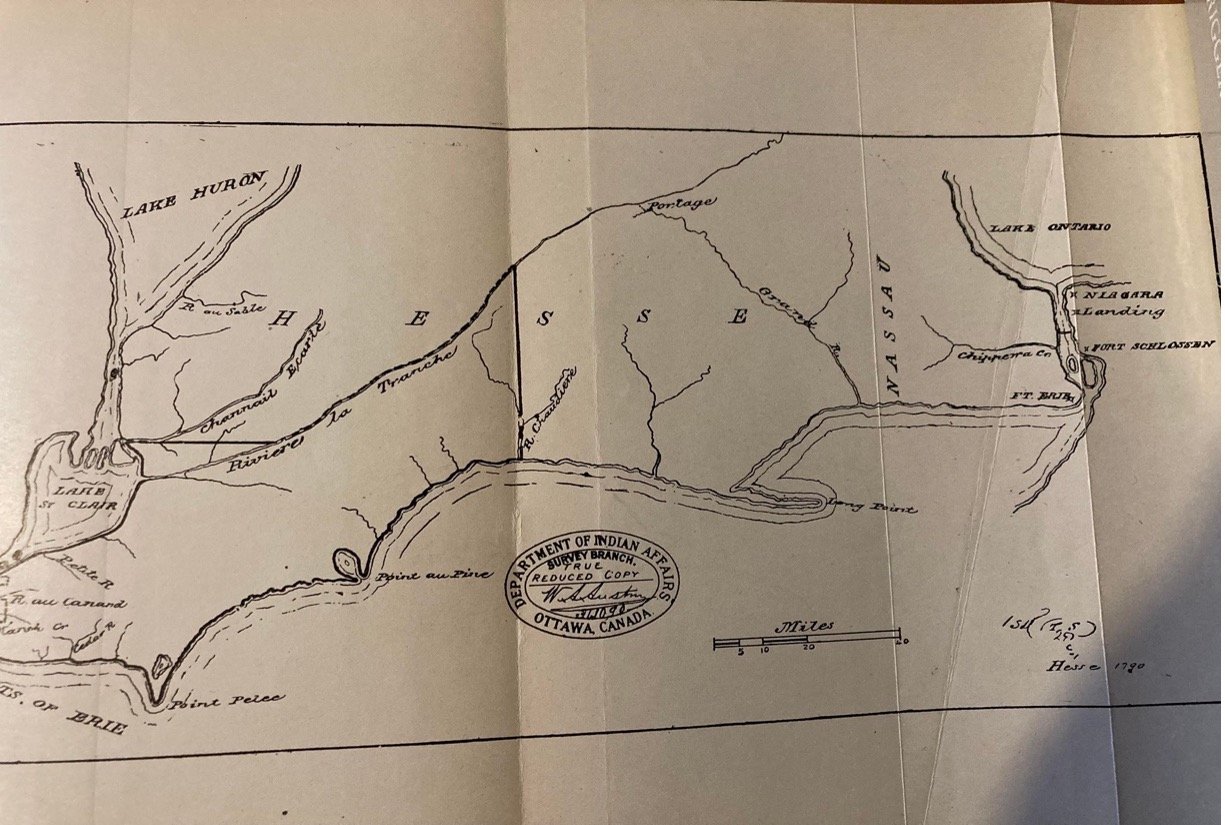

True reduced copy of original map to the “Mckee Treaty” of 1790, which included not only sovereign Anishinaabe Nation Bands (Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Ojibwe/Chippewa), but a sovereign Band of “non-Six Nation” Iroquois who are identified as Hurons.

This is admittedly an over-simplified story of a very small portion of Upper Canada. Our shared history is full of similar narratives about a land larger than any single group at the time could imagine. It is my hope that these web pages will be a small contribution to our shared learning about one another.

Sources

Indian Treaties and Surrenders: Vols. I & II. Indian & Northern Affairs Canada.

“Royal Proclamation 1763.” Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/

“Treaties and Huron County.” 2017. www.huroncountymuseum.ca/treaties-huron-county/

Yates, David. “County History.” Ontario Geneologial Society. Huron Branch. https://huron.ogs.on.ca/pre-settlement/#:~:text=The%20Attawandaron%20controlled%20southwestern%20Ontario%20from%20the%20Niagara,known%20about%20them%20is%20derived%20from%20outside%20sources